Avian coccidiosis in chickens is considered worldwide as one of the main diseases in poultry production, causing significant health problems and great economic losses, either in its clinical or subclinical form. In this article, we will briefly review the main features of the disease: etiologic agent, pathogenesis, prevention and control.

Etiologic agent of coccidiosis in chickens

The disease is caused by the replication at intestinal level of parasites belonging to the Genus Eimeria, which in turn is part of the Coccidia subclass and gives the disease its name.

Within this Coccidia subclass, we can find many other parasites that affect humans and animals, such as Isospora, Sarcocystis or Toxoplasma. And, although further away phylogenetically, Coccidia subclass also includes parasites of the genus Babesia, Theileria and Plasmodium, which cause malaria.

Focusing on the specific Eimeria species affecting domestic chickens and hens (belonging to the Genus Gallus gallus), 7 species have been confirmed so far. We highlight firstly E. acervulina, E. maxima and E. tenella, species that affect both young birds and long-living birds, and with a great impact on gut health.

There are two other species, E. mitis and E. praecox, which are considered as causing subclinical coccidiosis because they do not produce apparent clinical signs or intestinal lesions visible at the macroscopic level (but do histologically). Its greatest impact is shown as a reduction in broiler growth at early age.

The last two species of Eimeria are E. brunetti and E. necatrix, which cause the disease in long-living birds: laying hens and breeders. They produce severe injuries and significant mortality, especially in the case of E. necatrix.

Because of their slower biological cycle, these species do not affect broilers, which are usually slaughtered before the parasite reaches its maximum level of replication.

We will finish this section dedicated to the description of the causative agent of coccidiosis by showing you a video where the life cycle of the parasite, closely related to its pathogenicity and the development of immunity, is described.

Coccidiosis pathogenesis: symptoms of coccidiosis in chickens

In this next section we will briefly review the main aspects related to the pathology of coccidiosis disease, explaining how the birds are affected.

In birds that suffer an active Eimeria infestation, it will be very likely to find these various or all clinical signs that we will list below:

- Depressed birds, with reduced activity

- Birds huddled and with ruffled feathers

- Decrease in food intake

- Anaemia

- Dehydration

- Presence of diarrhea and loose stools (with mucus and/or blood)

- Mortality, which can be very high

- Harm on the productive performance of the birds, with worse zootechnical results: lower growth and less weight, reduction in egg production, etc.

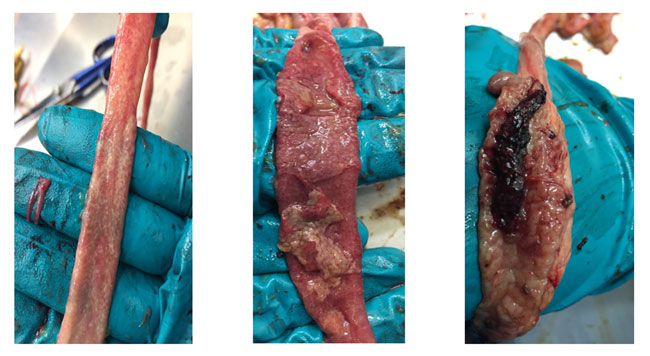

Because all these symptoms are non-specific and can lead to a wrong diagnosis of the disease, confirmation must be carried out through necropsies of the birds where the specific intestinal lesions produced by the different species of Eimeria are evaluated, and also their degree of severity following the Johnson & Reid scale.

Some examples of severe intestinal lesions produced by E. acervulina, E. maxima and E. tenella.

Some examples of severe intestinal lesions produced by E. acervulina, E. maxima and E. tenella.

Prevention and control of coccidiosis in chickens

We will end this introduction to the disease of avian coccidiosis with a section where we will review the main strategies to prevent and control the disease.

The first used method to prevent coccidiosis problems is of course the reduction of parasite load on farms, through biosecurity practices and by cleaning and disinfecting the houses and all the material that will come in touch with birds.

The objective is to minimize the number of resistance forms of the parasite, the oocysts, in order to reduce the infesting dose to which the birds will be exposed.

However, Eimeria oocysts are highly resistant, and are not affected by most of the commonly used methods. In spite of that, they are sensitive to certain physical agents, such as freezing, dryness and sustained high temperatures. It is also possible to reduce their number by fermentation, with heat and ammonia production.

By cleaning and disinfecting facilities, the total number of Eimeria oocysts will decrease, as well as the risk of bird infestation. However, it is not possible to achieve a total elimination of disease hazard.

Hot water and detergent agents should be used to clean and wash surfaces. Besides, quaternary ammonium compounds, peroxides, peracetic acid or phenols are shown being effective in disinfection against coccidia oocysts.

Going forward with more specific strategies to control coccidiosis, the most commonly used compounds nowadays are anticoccidial drugs. They can be classified into coccidiostats, included in poultry feed and with preventive action, and coccidicides, added to drinking water to be used as a treatment when clinical disease occurs.

However, the continued use of these drugs favors the development of resistances, failures in their effectiveness and the appearance of clinical and subclinical issues of coccidiosis.

Furthermore, its use at sufficiently high doses to be effective may pose a risk of contamination in the final product, meat and/or eggs, ants its subsequent condemnation.

Another important strategy for coccidiosis prevention is the use of live vaccines, which stimulate the development of a strong immunity in birds after their replication in the gut.

Vaccination against coccidiosis has proven to be a very effective and safe alternative, especially in the case of vaccine strains attenuated by precociousness. For this reason, more and more producers are turning to it as a method of disease control.

REFERENCES:

- H. D. Chapman “Milestones in avian coccidiosis research: A review” 2014, Poultry Science 93, pp. 501–511.

- W. M. Reid, “History of avian medicine in the United States. Control of coccidiosis” Avian diseases, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 509–525, 1990.

- Johnson J., Reid W.M., 1970. Anticoccidial drugs: lesion scoring techniques in battery and floor-pen experiments with chickens. Exp. Parasitology 28(1): 30-6.